Introduction

What is an Earthquake?

Why and Where?

Seismic Waves

How We Measure Them

Locating Earthquakes

Measuring the Size of an Earthquake

Intensity

The Structure of the Earth

The Biggest and the Deadliest

Earthquakes in the UK

Links to Seismology Information

Printable PDF of Earthquakes Booklet (2.7 MB) |

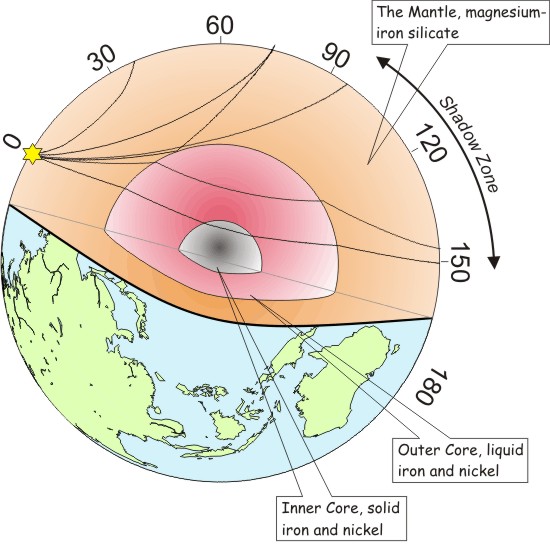

Most of what we know about the interior of the Earth comes from the study of seismic waves from earthquakes. Seismic waves from large earthquakes pass throughout the Earth. These waves contain vital information about the internal structure of the Earth. As seismic waves pass through the Earth, they are refracted, or bent, like rays of light bend when they pass though a glass prism. Because the speed of the seismic waves depends on density, we can use the travel-time of seismic waves to map change in density with depth, and show that the Earth is composed of several layers.

The Crust: this brittle outermost layer varies in thickness from 25 to 60 km under continents, and from 4 to 6 km under the oceans. Continental crust is quite complex in structure and is made from many different kinds of rocks.

The Mantle: below the crust lies the dense Mantle, extending to a depth of 2890 km. It consists of dense silicate rocks. Both P- and S-waves from earthquakes travel through the mantle, demonstrating that it is solid. However, there is separate evidence that parts of the Mantle behaves as a fluid over very long geological times scales, with rocks flowing slowly in giant convection cells.

The Core: at a depth of 2890 km is the boundary between the Mantle and the Earth's Core. The Core is composed of Iron and we know that it exists because it refracts seismic waves creating a “shadow zone” at distances between 103º and 143º. We also know that the outer part of the Core is liquid, because S-waves do not pass through it. |